RAF

PEVENSEY "CHAIN HOME" - THE HISTORY OF RADAR FARM

The

Pevensey levels was home to RAF Pevensey: Chain Home Radar Station, a

complex that spread widely across this Sussex marshland when owned by the

Ministry of Defence, now mostly in private ownership by farmers.

This was the world's first operational radar, hence, a significant

archaeological area.

Over

seventy years ago on February 26, 1935, a simple experiment in a field near Daventry conclusively demonstrated that

aircraft could be detected by

radio. The experiment arose directly from the need to prove, to a first order, calculations that suggested that if an aircraft was 'illuminated' by radio waves, enough energy should be 'reflected' to permit detection on the ground by a sensitive receiver.

As a result of this experiment a massive programme was begun. This had the highest priority and virtually unlimited finance, to design, build and install a chain of early warning systems around the coast of Britain. The importance of this courageous decision to a country whose only early warning of air attack was, at that time, a huge concrete acoustic mirror on the Romney marshes, cannot be over stated. Key stations in the south east of England were operational and integrated into a vast reporting network just in time for the air battles to come.

That makes a change, our Ministry of Defence are normally the last to

jump.

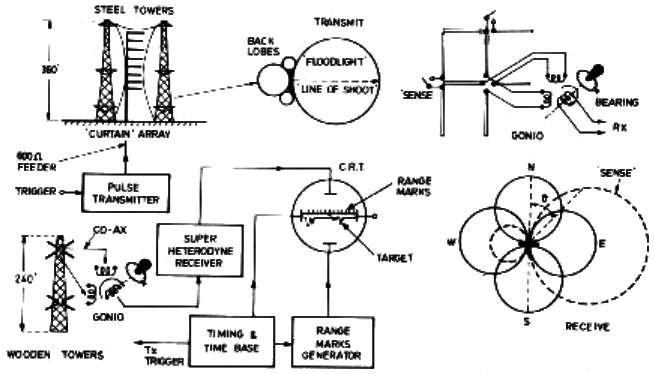

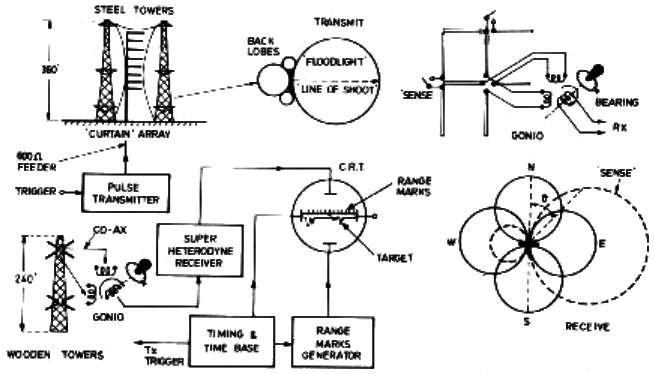

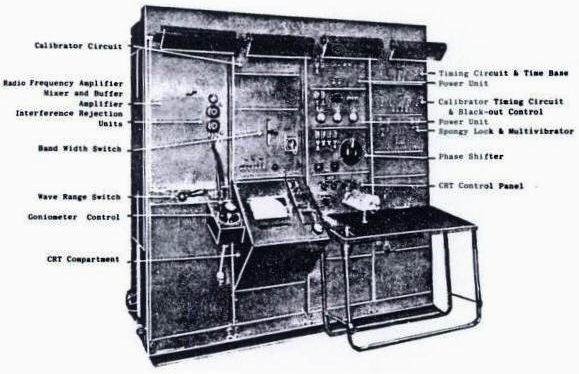

GENERAL PRINCIPLE

The basic operating principle of Chain Home is very simple: the volume of sky to be kept under surveillance is literally 'floodlit' with r.f. pulsed energy; the back-scattered pulses or echoes' from all aircraft within this volume are received back at the ground station by a set of crossed-dipoles connected to a low-noise, high-gain receiver and displayed as a Y-deflection along the time base of a CRT. The aircraft range is simply a precise measurement of the elapsed time between the transmitted pulse and the 'echo', and the bearing a measurement of the ratio of 'echo' strengths of the X- and Y-components of the crossed-dipoles. These principles are illustrated in figure1.

The huge CH aerial masts were clearly visible even from large distances, attracting the attention of German intelligence already in the years preceding the war. Surprisingly, the Germans did not discover their true purpose until 1940 but once they did, several attempts we made to bomb the RDF stations from the air. Pevensey was attacked this way on 12 August 1940 and temporarily put out of action. Fortunately, it took only 6 hours to bring it back on the air again.

CHOICE OF FREQUENCY, POLARIZATION AND P.R.F

The choice of radio frequency was principally influenced by three factors: the 'state of the art' technology in 1935, feasible antenna dimensions to provide the vertical polar diagram and antenna gain required for efficient floodlighting and heightfinding; and a wavelength that was considered at that time likely to give the best 'echo' from a typical bomber of the period. Very little, if anything, was known at that time about the effective back-scattering cross-section of an aircraft or how it varied with frequency.

It was earlier thought that an approaching aircraft could be regarded as a half-wave, horizontally polarized dipole; in fact, a typical enemy bomber of that period, a Heinkel 111 with a wingspan of 22.5 metres, closely matched the original 'Daventry Experiment' frequency of 6 MHz. This theory was later abandoned.

The original plan was for each station to have the choice of operating on any of four allocated spot frequencies in the band 20 to 55 MHz as a counter-measure to possible jamming and as alternative frequencies should interference or propagation effects cause operational problems.

Typical

of the tracks on the marshes that were made to be able to build the

structures and also to be able to service the installations. Concrete was

used extensively, because it is quick and reliable. Over the years, tracks

that are not used become overgrown. Many a farmer has dug down to discover

that he owns a bit of wartime history. Our advice if that happens to you

is to photograph the area comprehensively. You will find that the likes of

Natural England, are the enemy of military archaeology, paying lip

service, while pursuing an agenda to rid the countryside of these valuable

artifacts - such as to pave the way for a return to marshland and pre 1935

status. See the case of the local hotelier: Mr

Gulzar as reported in the Eastbourne

Herald in September 2013. He had spent a lot of money to uncover and

recondition an old WWII track, which we would applaud, only to be fined

and told to remove such track(s) - without any input from the experts.

Natural England, who know nothing about archaeology, set themselves up as

Judge and Jury in seeking leave of the Court to Order removal of any

archaeological features on the land. What is a mystery to us, is how the

Court allowed that!

BUILDING

THE CHAIN

As

a follow on from the development of radar at Orfordness and at the Bawdsey Research Station in Suffolk

the Air Ministry established a programme of building radar stations around the British coast to provide warning of air attack on Great Britain. A survey was undertaken in 1938 to assess the suitability of the local terrain for Air Defence Radar operations with the first of these new stations coming on line by

1939. This network formed the basis of a chain of radar stations called CHAIN HOME

(CH), the nearest being RAF

Wartling.

These stations consisted of two main types; East Coast stations and West Coast stations. The East Coast stations were similar in design to the experimental station set up at Bawdsey in 1936. In their final form these stations were designed to have equipment housed in protected buildings with transmitter aerials suspended from 350' steel towers and receiver aerials mounted on 240'

timber towers.

The West Coast stations differed in layout and relied on dispersal instead of protected buildings for defence. Thus the West Coast stations had two transmitter and receiver blocks with duplicate equipment in each. Transmitter aerials were mounted on 325' guyed steel masts with the receiver aerial mounted on 240' timber towers.

The majority of Chain Home stations were also provided with reserve equipment, either buried or remote. Buried reserves consisted of underground transmitter and receiver blocks, each with three entrance hatches (two for plant and one for personnel) set on steel rollers. Nearby were the emergency exit hatch, ventilation shafts and 120' wooden tower carrying the aerials. On some stations the transmitter and receiver buried reserves were together on an adjoining site (often the next

field). At others the two buried reserves were separate but located close to their respective above ground building. Many of the West Coast stations had remote reserves some distance from the main station but utilising similar above ground transmitter and receiver blocks.

Most stations were powered from the National Grid but they were also provided with generators to cover interruptions in the mains electricity supply. These were located in another protected building known as a stand-by set house. These were similar in design to the transmitter and receiver block although smaller and were of brick construction and surrounded by a traverse (earth banks) for blast protection.

RAF

PEVENSEY

The East Coast Chain Home station at Pevensey was built in 1939. It was originally intended to build the station at Fairlight, east of Hastings but the local landowner objected, considering the aerial masts to be unsightly. In order to provide the same coverage as the proposed station at Fairlight two new stations were required one at Rye and the other at Pevensey. Pevensey was the worst site in the southern group as the whole area was flooded and the buildings were sited in silt subsoil and continuous pumping was needed during the construction. Pevensey faced south (line of shoot) for attack across France from Germany. It was in the right position for the

Battle of Britain.

As East Coast stations have only one channel, emergency mobile radars (MRU's) were positioned near each Chain Home station. That for Pevensey was at Chilley Farm to the south west.

As first built, RAF Pevensey covered a considerable area of the Pevensey Levels, now Pylon Farm, but the transmitters and receivers were housed in sandbagged wooden huts with 90' guyed wooden masts and a mobile generator. This was known as an advanced Chain Home prior to the building of a permanent station.

Upon completion of the standard East Coast station, the operations blocks gave a much higher level of protection against attack. These were of brick, built on the surface but surrounded with a traverse and topped with a six foot thick shingle filled

concrete sandwich roof. Shortly after completion the blast from a German bomb dislodged several tons of shingle, some of it falling into the receiver building; the damaged ceiling is still clearly visible today.

RAF Pevensey was one of the original 20 Air Ministry Experimental Stations. As originally planned there should have been four 360 foot steel transmitter towers spaced 180ft apart and four 240ft wooden receiver towers in a rhombic pattern set at a distance from the transmitters.

At Pevensey however there were originally four transmitter towers but No. 1 tower was later dismantled and re-erected in the far north. This was because of the urgency involved in the Chain Home programme, the 'state of the art' of prewar radio technology and the shortage of steel. It was originally planned that each station would operate on four spot frequencies in the 50-20 MHz range, (6-15 metre wave length), with the transmitting aerials suspended between the platforms at 50, 200 and 350 feet.

However, it was soon found that the radiation pattern was not as good as it theoretically should have been and to overcome the difficulty, a larger curtain array of dipoles and reflectors, suspended on high tensile steel cables slung between towers, was the answer. At the same time it was decided that four frequencies per station would lead to delays and was, in any event, unduly optimistic of achievement. The number of frequencies was reduced to two in the 30-22 MHz range, (10 -13.5 metre bands). As two suspended arrays could be supported between three towers, (the middle one being common to both arrays), those stations still under construction would have one tower deleted from the original plan even if four bases had been cast.

Chain Home was at the forefront of a reporting network resulting in warning data being forwarded to the Fighter Command filter room at Bentley Priory where it was analysed and displayed on the Fighter Command operations table. The information was then told to the Fighter Group HQ's from where the controller allocated the raids to be intercepted from sector airfields and controlled by the sector operations centre during the day and the fledgling GCI radar stations during darkness. The new GCI station, RAF Wartling, built on the opposite side of the road to RAF Pevensey is an example of this, becoming operational during the early years of WW2.

RAF Pevensey was short lived and by December 1945 the station was described as 'caretaking' (Air 25/686 Appendix A) with its future also listed as 'caretaking'. As the station was not required for the post war rotor radar programme both

RAF Pevensey and RAF Rye were offered for sale by public auction in

Battle (Sussex) in November 1958. The inventory of buildings and equipment offered for sale at the two sites was listed as 'Brick sectional

timber and handcraft buildings, 6 350 foot steel towers, 2 water towers and the contents of the buildings including 2 Mirrlees 102 hp diesel engines, electrical equipment and all fittings, steel and timber doors and windows, air ventilation systems, fuel and water tanks, sewage pumps, electric motors, tubular wall heaters, RSJ's, baths, sinks and power cables'.

MEMORIES

OF SGT. JEAN (SALLY) SEMPLE - TRACKING

THE LUFTWAFFE

Jean Semple had to watch the early type RF5 screen with a hairy RAF blanket thrown over her head as the cathode ray tube was weak and therefore hard to see.

On her very first day of operation, in 1940, at Pevensey, she saw on her screen a large number of what were probably Heinkels and Dorniers. She informed her (male) supervisor and suggested he take over but he said: ‘It’s Your Operation, you do it.’

At this early time there was no pressing of buttons. You worked out your own plots. It was hard to count the exact number of planes as they were all coming together and going up and down – which is called beating. You don’t see a separate blip for each one when there’s a lot bunched together.

Jean counted the number of aircraft as an unprecedented 200 plus. She and her supervisor reported the sighting to Stanmore, which could hardly believe Jean’s figures. Could they be dealing with migrating birds?

The plotter in the filter room at Stanmore said she would have to seek verification from her scientific observer who was looking down on the plotting from the window above. Jean was proved to be right. Not birds but planes. Nearly 200 enemy planes.

In those early days at Pevensey you were able to speak to the pilot. Both the operatives and the pilots used nicknames. One character who was often called upon at that time was Blood Orange Smith. Blood Orange was meant to be a reconnaissance pilot but often got bored and went after the enemy. He always came back safely.

You had to plot outgoing friendly planes as well as incoming enemy ones. Distinguishing between the two was another difficulty inherent of the early CH operations, but by the time of the Battle of Britain, RAF combat aircraft carried special ID system called IFF. Jean explains:

‘If we were sending up fighters into the heart of the battle you could be plotting one of your own planes believing it was the enemy, so you needed an ID to establish that they were friendly. This was called IFF – Identification, Friend or Foe.’

At a later point, Jean returned to Bawdsey in an operational capacity. At this time Stanmore decided that their own personnel would benefit from knowing where their plots were coming from and arranged a two-week exchange. Thus my sister found herself seated at the famous board in Stanmore’s filter room. She remembers:

’There was a Halma Clock on the wall. Its face was divided into colours. Time was divided into colours. There was never more than 2-1/2 minutes of plotting on the table at one time because everything was moving so quickly.

A number of people looked down at the plotting from the windows above. The scientific observer, of course, plus VIPs, the

BBC, representatives of the Army and Navy, members of the Observer Corp and, frequently, Lord Dowding himself wearing full uniform and, I was told, his carpet slippers.’

Jean still has a photograph of Betty Smith, the girl she made the exchange with, who she believes went on to become a film actress.

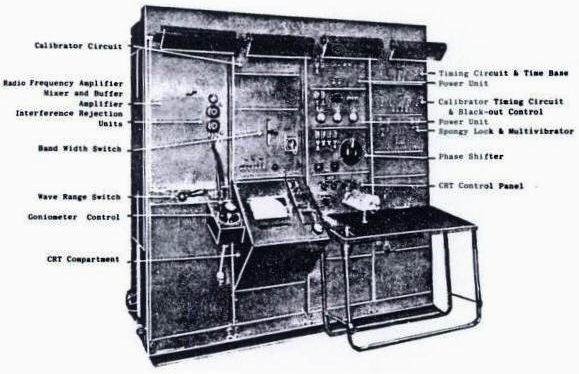

RADAR IMPROVEMENTS

As the war progressed, many modifications and improvements were made to the original equipment, although its basic modus operandi remained the same. In due course Jean moved onto the more sophisticated RF7. This had a vastly improved cathode ray tube that allowed her to throw off the hairy blanket and watch her screen in a more convenient way. Jean still has a drawing that she made of an RF7.

With the newer equipment you could provide a signal that an Allied pilot could switch onto if need be. For instance, in the event that he had broken away from the squadron and lost his bearings. This signal could only be used as a last resort as it could be picked up by the Germans.

In early RF7 days, at one station, 11 and 12 Group operated a system called Spotted

Dog. Set next to the observer was a large console about four-foot-square covered with Perspex. Jean remembers:

‘Laid out on the console under the Perspex was our section of a map of Britain. The Perspex itself was marked with an ordinance grid reference. The console had a gadget, connected to a range finder. This gadget was an illuminated spot the size of a farthing.

Once the operator had an optimum reading they would stop the gadget. A person standing beside the operator with a clipboard wrote down time, seconds and plot. Another person turned to the console and marked the position on its ordinance grid with a grease pencil. Meanwhile, the observer made speech contact with the filter room at Stanmore.

All the plots recorded on the clipboard were later transferred to another map. The idea was to see where, in principal, all the dots were collecting and where they were not. In the end you had big patches of dots and other areas where there was nothing. You could draw a line round the big patches of dots, like a balloon. These were called lobes. The areas remaining would be the blind spots that Jerry could take advantage of. ‘

Connected to the Radar Station’s four aerials was the Parent Unit, the Plan Position Indicator. The PPI’s parabolic reflector resembled our modern satellite dishes. There was a little tube in the centre of it, which was hollow. No one seemed to know why it worked, but it did. The PPI was connected to a cathode ray tube that produced not a thin line but a wide sweep. This system adequately covered the lobes and the vulnerable gaps between the lobes. In due course a curtain array was, including 100-foot dipoles that could be energised at will.

Another procedure to ensure accurate observing and plotting was by use of a theodolite. A rigger would climb the 340-foot steel aerial with the theodolite. Meanwhile, an autogiro would be flying at a pre-determined height and bearing. The theodolite then took the true reading of the height and bearing of the autogiro. Its results would be picked up on the CH cathode ray tube and compared with the less accurate Goniometer plot. The discrepancy would be declared a percentage of a pure rose, and would be drawn as, for instance, a 90 to 95% distorted rose and allowances could then be made for the differential. After a while, this work became automated with the help of RAF General Post Office equipment and personnel working from a sub-station.

By 1943, the bomber offensive was in full swing and with it, the aerial operations intensified beyond recognition. Jean remembers:

‘As war progressed we were sending up 1000 bombers at any one time and they all had to be plotted. The plotting was enormous for 1000 bombers so we had to divide our maps into four. Taking each quarter you tried to give four readings, an inner and an outer reading both of bearing and of range. We’d start with a mean range, appearing like a range of mountains, with inner and outer edges and four corners. Sometimes the planes were miles apart.’

Jean (Sally) Semple achieved the rank of Sergeant and had the chance to go further, having been twice recommended for a commission.

Marriage intervened, however, and she left the service with a Clause 11 discharge – pregnancy. Her friendships with fellow Radar Operators continued into civilian life with her closest colleague, Joan Pile, dying only a short time ago. Jean and her husband

moved from the Welsh countryside to a pleasant town house close to leisure amenities.

Published in 2010.

During

the 2nd World War, the Pevensey Levels hosted an underground radar

tracking station. The emplacements seen in the photograph above were to

protect the early warning station from land attack. The underground

installation was flooded the last time our local historian visited. These

remains are of historic importance. The above ground buildings on the

adjacent hill have been converted to residential use. Those seen above are

roughly half way between Bunker Hill and RAF Pevensey.

Many

of the superb photographs on this subject were taken by Nick Catford. We

apologise in advance to Mr Catford, if our versions have been digitally

altered to fit within our parameters. Without his persistence and

dedication there might not have been a record that future generation might

enjoy. We know though, that this subject fascinates many people, both

locally and nationally - as a reminder that when the chips are down, that

the UK

takes home security seriously. You can contact Nick, via Subterranea

Britannica: Membership Secretary - Nick Catford - 13 Highcroft Cottages, London Road,

SWANLEY, BR8 8DB, United Kingdom. Email: membership@subbrit.org.uk

RAF PEVENSEY TODAY

RAF Pevensey is located on Manxey Level, a part of the Pevensey Levels, half a mile to the west of the Pevensey to Wartlng Road. The site is entered at the end of a dead end public road. The original gate posts still stand and just inside the gate there is an air raid shelter on the left hand side of the road and the two Air Ministry wardens houses on the right hand side of the road; these are now renamed Pylons Cottages. After 200 yards Pylons Farm house stands on the right hand side of the road. The farm house is a modern bungalow standing on the site of the transmitter block which was demolished in December 1987. A concrete guying anchorage point can be seen in the field beyond the farm house. It is unclear what purpose this served as the transmitter towers were not guyed.

RAF

Pevensey - receiver room, brick and concrete construction. Note that the

windows have been bricked up. It is unclear when, since the paint scheme

appears to match in places.

The original concrete road continues in a south westerly direction towards the receiver block which can be seen in the distance. After a further 100 yards a road turns off to the east, opposite this junction there is another air raid shelter on the south side of the road, the front has been removed and it is now used as a store.

When visited in 1987 this was still standing and in good condition but today it has changed out of all recognition. The brick built stand-by set house has been demolished leaving the blast walls that surrounded the building. The southern wall has been removed to create an open front and a new hipped roof was added in 2003. The earth banks surrounding the blast walls have also been largely removed. The building is now used as a farm machinery store.

The main spine road carries on in a south westerly direction passing another air raid shelter on the left and the foundations of other buildings on the right. After a further 150 yards the receiver block is reached. This is the only one of the three protected blocks still standing in anything like its original condition. The block still retains its earth traverse with two ways through to a ring path around the outside of the brick building. Inside the building the partition walls are still in place maintaining the original room layout although all the rooms have been stripped of any original fittings. The floorboards in the main spine corridor have also been removed making access through the difficult as the underfloor area is flooded.

The main tiled receiver room is at the north west end of the building, this has a long rectangular open cable duct in the floor. The ventilation plant room has a number of small concrete beds. There is ventilation trunking in the building with some sections of it lying on the floor. On the south side of the building there is a Stanton air raid shelter which is flooded.

The four receiver tower bases are arranged in a rhombic pattern around the operations block, each of them consisting of four large concrete bases each supporting one leg of the tower. Underneath the southern tower are the collapsed remains of the original IFF hut. A concrete path runs south from the operations block to the collapsed remains of the later IFF hut.

The two buried reserves are 75 yards apart in a field 150 yards to the south of the main spine road. The transmitter buried reserve to the east has four concrete bases for the transmitter tower.

Close by are the three concrete hatches mounted on rollers flush with the ground. The larger pair were for plant and the smaller hatch which opens on to a steel stairway was for personnel. None of the hatches will now move but there is sufficient space to see through and the bunker is flooded just below the middle landing on the stairway. When visited in 1987 it was possible to open the hatch and descend the ladder down to the floodwater. Close by there are the remains of two ventilator towers and the hatch for the emergency exit. This has been capped with a concrete block.

The receiver buried reserve to the west leaves identical remains but is flooded to within a couple of inches of the surface.

A number of concrete foundations from other buildings can be seen scattered around the site.

RAF

Herstmonceux - This is now a science museum dedicated to the occupiers

over the years and the early electricity generating industry. Herstmonceux

Museum was put on a Monument Protection Programme by English

Heritage around 2000. The generating rooms are well over 100 years

old, which, for a building of timber construction without modern pressure

chemical treatments, is something of a miracle. A big problem in the

Wealden area is that the local council do not keep a list of buildings of

historic importance, ranking their duty to protect archaeological remains

as a low priority. This may be because they are too busy spending tax

dollars enforcing to keep buildings such as that above, without any

reasonable beneficial use. Incredibly, that is what the council did in

this case, spending an estimated £500,000 and rising on around 190

enforcement visits, one Crown Court case and five High Court cases - only

to be proved wrong in the end by an exceptionally resilient

eco-warrior.

HERSTMONCEUX

MUSEUM

Readers

might be interested to know that about 5 miles further inland, Lime Park

was host to the RAF, with wounded airmen being billeted within the old

generating rooms, now known as Herstmonceux

Museum. On this site were found the remains of a radio transmitted,

including battery banks (not connected with electricity generation for the

village), Morse code sending apparatus, all located near to a concrete

Anderson Shelter that survives to this day, though is in danger of being

altered. This might then be described as RAF Herstmonceux.

LINKS

& REFERENCE

http://www.independent.co.uk/the-real-scandal-behind-horsemeat-is-the-struggle-of-smallholding-british-farmers

http://www.farmersguardian.com/home/business/princess-anne-calls-for-uk-horsemeat-market/60182.article

http://www.equinerescuefrance.org/campaigns-2/horsemeat-in-france/

https://www.gov.uk/keeping-horses-on-farms

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1550742/We-should-eat-horse-meat-says-Ramsay.html

http://www.fwi.co.uk/business/horsemeat-scandal/

http://www.nationalgrideducation.com/

http://www.subbrit.org.uk/sb-sites/sites/p/pevensey_chain_home/index.shtml

http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/

English

Heritage

Bob Jenner

A Sussex Sunset by Peter Longstaff-Tyrrell ISBN 0 9521297 0 1 published by Gote House Publishing

20th Century Defences in Britain ISBN 1 872414 57 5 published by Council For British Archaeology