|

V

V

HE'S

BACK.

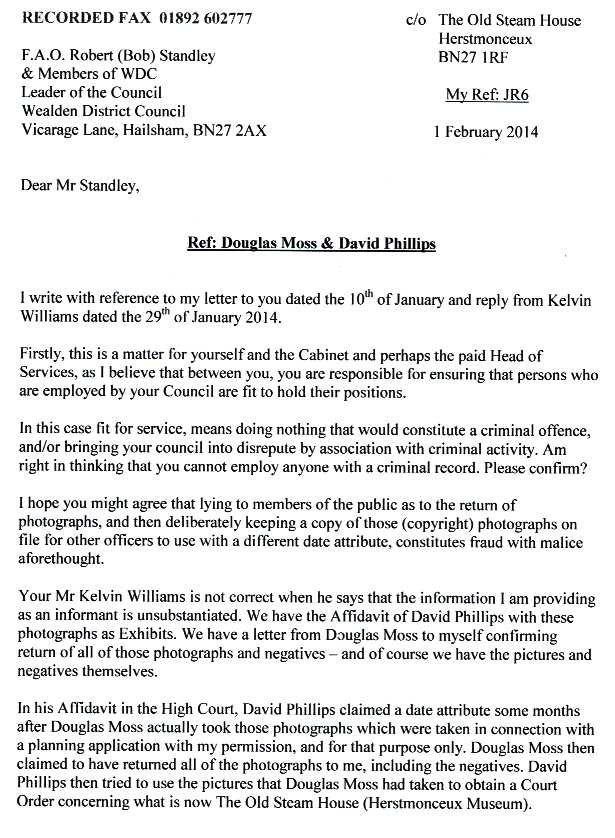

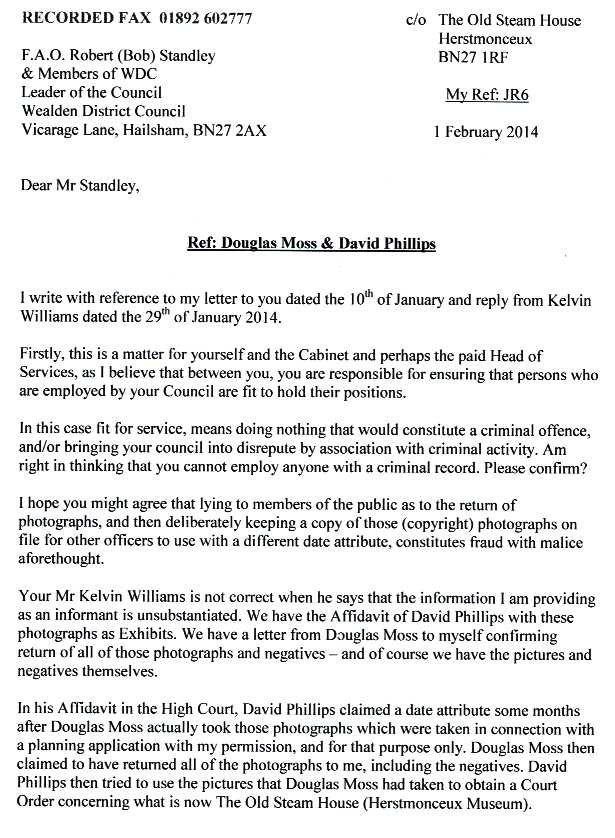

Nelson blows the whistle: Dear

Cllr Standley, Please investigate the fact that you appear to still have two

officers in your Council who have been guilty of attempting to pervert the course

of justice - or maybe worse. This has been brought to the attention of various

Heads of Paid Services, but to date, apart from trying to buy Mr

Kruschandl off

with an Agreement as to recognition of the archaeology of The Old Steam

House (now breached) - your Council appears never to have investigated these issues,

nor reported them to the proper authorities for investigation, or passed

them through your complaints procedure - if indeed you have such a

procedure? We also

note that Mr Phillips and

Mr Moss have never

publicly denied the offences of

which they stand accused. Nor has Mr Kruschandl ever received an

official explanation for the unlawful use of his copyright ©

photographs.

|

|

|

|

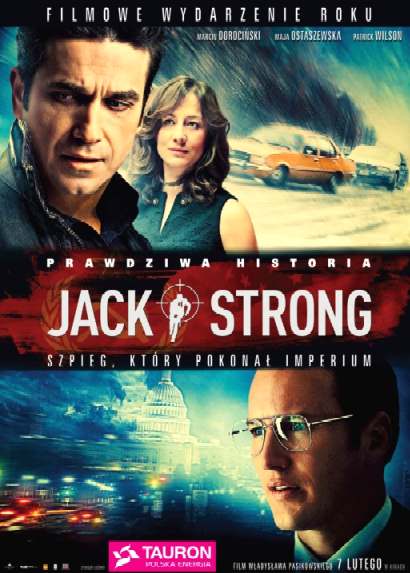

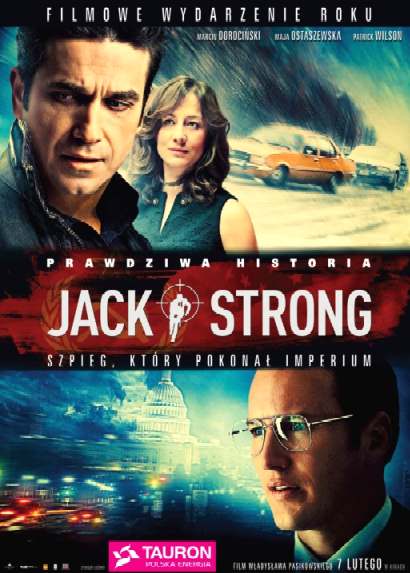

A whistleblower (whistle-blower or whistle blower) is a person who exposes misconduct, alleged dishonest or illegal activity occurring in an organization. The alleged misconduct may be classified in many ways; for example, a violation of a law, rule, regulation and/or a direct threat to public interest, such as fraud, health and safety violations, and corruption. Whistleblowers may make their allegations internally (for example, to other people within the accused organization) or externally (to regulators, law enforcement agencies, to the media or to groups concerned with the issues).

You may have statutory protections, but seriously corrupt

officials can always get you another way. See Julian

Assange |

PUBLIC INTEREST DISCLOSURE ACT 1988

The Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998 (c.23) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that protects

whistleblowers from detrimental treatment by their employer. Influenced by various financial scandals and accidents, along with the report of the Committee on Standards in Public Life, the bill was introduced to Parliament by Richard Shepherd and given government support, on the condition that it become an amendment to the Employment Rights Act 1996. After receiving the Royal Assent on 2 July 1998, the Act came into force on 2 July 1999. It protects employees who make disclosures of certain types of information, including evidence of illegal activity or damage to the environment, from retribution from their employers, such as dismissal or being passed over for promotion. In cases where such retribution takes place the employee may bring a case before an employment tribunal, which can award compensation.

As a result of the Act, many more employers have instituted internal whistleblowing procedures, although only 38 percent of individuals surveyed worked for a company with such procedures in place. The Act has been criticised for failing to force employers to institute such a policy, containing no provisions preventing the "blacklisting" of employees who make such disclosures, and failing to protect the employee from libel proceedings should his allegation turn out to be false.

HISTORY

Prior to the 1998 Act, whistleblowers in the United Kingdom had no protection against being dismissed by their employer. Although they could avoid being sued for breach of confidence thanks to a public interest defence, this did not prevent subtle or open victimisation in the workplace, including disciplinary action, dismissal, failure to gain promotion or a pay rise. During the early to mid-1990s, interest in whistleblower protection grew, partially because of a series of financial scandals and health and safety accidents, which investigations into showed could have been prevented if employees had been permitted to voice their concerns, and partially because of the work of the Committee on Standards in Public Life. In 1995 and 1996, two private member's bills dealing with whistleblowers were introduced to Parliament, by Tony Wright and Don Touhig respectively, but both efforts fell through. When Richard Shepherd proposed a similar bill, however, he got government support for it on the condition that it be an amendment to the Employment Rights Act 1996 rather than a new area of law in its own right. Public Concern at Work, a UK-based whistleblowers charity, was involved in the drafting and consultation stages of the bill.

The Public Interest Disclosure Bill was introduced to the House of Commons by Shepherd in 1997, and given its second reading on 12 December before being sent to a

committee. After being passed by the Commons it moved to the House of Lords on 27 April 1998, and was passed on 29 June, receiving the Royal Assent on 2 July and becoming the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998. Originally scheduled to come into force on 1 January 1999, the Act instead became applicable law on 2 July.

FLUSHED

WITH SUCCESS - We

imagine that Wealden would have been overjoyed in duping the High Court

into making an Order that demanded removal of toilet facilities from their

long-term adversary's home, condemning him to defecate in the old

fashioned way - and remarkable is it not how well an animal can adapt and

build from sheer determination until it is time to reveal the truth and

his gleaming new urinals.

The building has toilets re-fitted of course

thanks to Dame

Butler-Sloss, who in effect helped the victim potty-train

this naughty council. Naughty, naughty council. The occupiers rejoice with each pull of the handle, at the resourcefulness

of this underdog when the chips were down. The frivolity at Wealden's

offices was short lived when the Health & Safety Executive chimed in

to spend a penny or two. From that point on Wealden have been bogged down

with the publication of what they had done - and permanent skidmarks in

the underpants of their hall of shame. No amount of toilet tissue can ever

wipe the brown from this council's back passages - and nobody in this

council blew the whistle - the members and junior officers were so

frightened and brain washed by their bosses!

Yes,

officers

and members just stood by and let this happen - meaning of course that

there is no effective safety net within the council to stop senior

officials from carrying out acts against another human being with

deliberate malice. They probably need new members to take

control of new officers. This time officers and members who have a

higher moral code and some back-bone to stand up to bully-boy officers

and/or members who have ruled the roost for far too long.

THE ACT

Section 1 of the Act inserts sections 43A to L into the Employment Rights Act 1996, titled "Protected Disclosures". It provides that a disclosure which the whistleblower makes to their employer, a "prescribed person", in the course of seeking legal advice, Ministers of the Crown, individuals appointed by the Secretary of State for this purpose, or, in limited circumstances, "any other person", is protected. In addition, the disclosure must be one which the whistleblower "reasonably believes" shows a criminal offence, a failure to comply with legal obligations, a miscarriage of justice, danger to the health and safety of employees, damage to the environment, or the hiding of information which would show any of the above actions. These disclosures do not have to be of confidential information, and this section does not abolish the public interest defence; in addition, it can be the disclosure of information about actions which have already occurred, are occurring, or could occur in the future. In Miklaszewicz v Stolt Offshore Ltd, the Employment Appeal Tribunal confirmed that the disclosure does not have to have been made after the Act came into force; it is sufficient for the dismissal or other persecution by the employer to have happened after that time.

The list of "prescribed persons" is found in the Public Interest Disclosure (Prescribed Persons) Order

1999, and includes only official bodies; the Health and Safety Executive, the Data Protection Registrar, the Certification Officer, the Environment Agency and the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry. An employee will be protected if he "makes a disclosure in good faith" to one of these people, and "reasonably believes that the relevant failure...is a matter in respect of which the person is prescribed and the information is substantially true". Other prescribed persons include the Scottish Environment Protection Agency, in relation to "acts or omissions which have an actual or potential effect on the environment...including those relating to pollution".

If an employee does make such a disclosure, Section 2 inserts a new Section 47B, providing that the employee shall suffer no detriment in their employment as a result. This includes both negative actions and the absence of action, and as such covers discipline, dismissal, or failing to gain a pay rise or access to facilities which would otherwise have been provided. If an employee does suffer a detriment, he is permitted to make a complaint before an employment tribunal under Section 3. In front of an employment tribunal, the law is amended in Sections 4 and 5 to provide compensation, and to reverse the burden of proof; if an employee has been dismissed for making a protected disclosure, this dismissal is automatically considered unfair. Similarly, under Section 6, an employee cannot be given priority when discussing redundancies simply because he made such a disclosure. These sections take into account Section 7, which notes that there is no requirement of age or length of employment before they come into effect.

Under Section 8, the Secretary of State could pass a statutory instrument setting out the rules and limits surrounding compensation for the employee's dismissal after making a protected disclosure; until this is done, Section 9 provided interim remedies, which were the same as in other cases of unfair dismissal. The Secretary of State did pass such an instrument, the Public Interest Disclosure (Compensation) Regulations 1999, but Section 8 has now been repealed under Section 44 of the Employment Relations Act 1999. Under Section 10, the Act applies to crown servants, excepting under Section 11, those who are employees of MI5, MI6 or GCHQ. The Act does exclude, in Sections 12 and 13, serving police officers and those employed outside the United Kingdom.

STRATEGIC IMPACT

Terry Corbin, writing in the Criminal Law and Justice Weekly, notes that the result of the Act has been that many more employers have developed internal processes for reporting issues; partially due to their desire to fix problems before they become publicly reported, and partially because if an employee chooses to not use these processes and instead act under the 1998 Act, there is a greater chance the employer can depict his behaviour as "unreasonable". However, a survey done by Public Concern At Work showed that in 2010, only 38 percent of those surveyed worked for companies with whistleblowing policies in place, and only 23 percent knew that legal protection for whistleblowers existed. The number of cases brought by whistleblowers to employment tribunals has increased by over a

thousand-fold, from 157 in 1999/2000 to 1,761 in 2008/9.

David Lewis, writing in the Industrial Law Journal, highlights what he perceives as weaknesses in the legislation. Firstly, it does not force employers to make a policy relating to disclosures. Secondly, it does not prevent employers from "blacklisting" and refusing to hire those who are known within the industry to have made disclosures in previous jobs.

The complexity of the law was also

criticized, as was the fact that, if such a disclosure turns out to be incorrect, the employee may be sued for libel by his

employer, an issue now corrected in the USA by the 2010 Whistleblower

Protection Act - but still an issue in the UK. Volunteers and self-employed people are not covered, nor are those who, in disclosing the information, commit a criminal offence. At the

moment the law does not make any provision for psychological harm caused by whistleblowing, which research shows is an increasing likelihood.

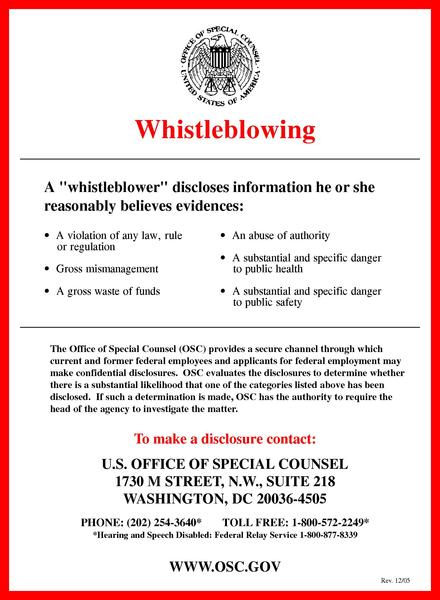

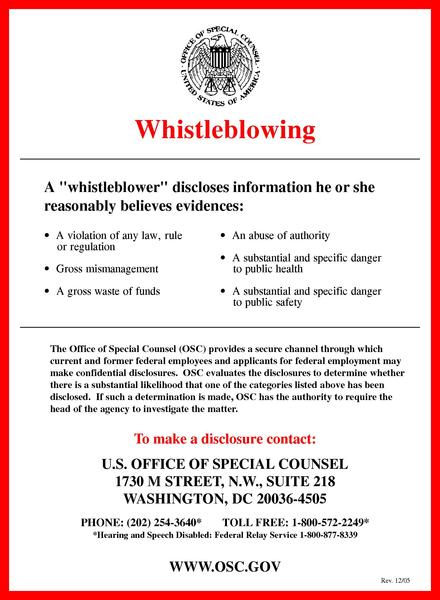

Clearly,

we need stronger protection for whistleblowers in the United Kingdom and

we hope that all politicians reading this message will take steps to

bring domestic legislation in line with the more enlightened policies in

the USA.

THE

WHISTLEBLOWER PROTECTION ACT 2010

As an initiative to fight corruption, the Whistleblower Protection Act 2010 (Act 711) has been duly approved in

Parliament on 6th May 2010 and came into force on Wednesday 15th December 2010.

This Act is to be implemented by all enforcement agencies eg: Police Force, Customs, Immigration, Malaysian Anti Corruption Commission etc., including ministries and departments under federal and state governments with investigative and enforcement authority.

The Act is formulated to encourage informers to expose corrupt practices and other misconduct. This move would provide immunity to informers from civil or criminal charges.

We support the Government’s urge that anybody who has any report to make, need not worry as under Section 7(1), a whistleblower shall have protection of confidential information, immunity from civil and criminal action, and protection against detrimental action.

We congratulate the Government for finally implementing this Act. With the enforcement of this Act, we hope that integrity and professionalism among workers in all sectors, both private and government, would be increased accordingly.

Under section 6 of the Whistleblower Protection Act 2010 “Whistleblower” is defined as “any person who makes a disclosure of improper conduct to the enforcement agency ”. Under Section 6(1) of the Act, it is stated that a person may make a disclosure of improper conduct to any enforcement agency based on his reasonable belief that any person has engaged, is engaging or is preparing to engage in improper conduct Provided that such disclosure is not specifically prohibited by any written law.

Section 6(2) further states that a disclosure of improper conduct under subsection (1) may also be made although the person making the disclosure may not be able to identify a particular person to which the disclosure relates or although the improper conduct has occurred before the commencement of this Act.

Information acquired of any improper conduct of the said person while he was an officer of a public body or an officer of a private body is also relevant.

US

WHISTLE BLOWING POLICY

In the United States, legal protections vary according to the subject matter of the whistleblowing, and sometimes the state in which the case arises.

The Continental Congress enacted the first whistleblower protection law in the United States on July 30, 1778 by a unanimous vote. The Continental Congress was moved to act after an incident in 1777, when Richard Marven and Samuel Shaw blew the whistle and suffered severe retaliation by Esek Hopkins, the commander-in-chief of the Continental Navy. Congress declared that the

United States would defend the two whistleblowers against a libel suit filed against them by Hopkins. The Continental Congress also declared it the duty of "all persons in the service of the United States, as well as all other the inhabitants thereof" to inform the Continental Congress or proper authorities of "misconduct, frauds or misdemeanors committed by any officers in the service of these states, which may come to their knowledge."

Seventy-five years after the ratification of the Constitution, as the Civil War rended the United States, Congress enacted one of the first laws that protected whistleblowers, the 1863 United States False Claims Act (revised in 1986), which tried to combat fraud by military suppliers. The act encourages whistleblowers by promising them a percentage of the money recovered or damages won by the government and protects them from wrongful dismissal.

Whistleblowers frequently face reprisal, sometimes at the hands of the organization or group which they have accused, sometimes from related organizations, and sometimes under law.

Questions about the legitimacy of whistle blowing, the moral responsibility of whistle blowing, and the appraisal of the institutions of whistle blowing are part of the field of political ethics.

* Lloyd-La Follette Act (1912)

* Water Pollution Control Act (1972)

* Safe Drinking Water Act (1974)

* Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (also called the Solid Waste Disposal Act) (1976)

* Toxic Substances Control Act (1976)

* Energy Reorganization Act of 1974 (through 1978 amendment to protect nuclear whistleblowers)

* Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA, or the

Superfund Law) (1980)

* Clean Air Act (1990)

* Surface Transportation Assistance Act (1982)

* Pipeline Safety Improvement Act (PSIA) (2002)

*

Wendell H. Ford Aviation Investment and Reform Act for the 21st Century (“AIR 21″)

*

Sarbanes-Oxley Act (2002) (for corporate fraud whistleblowers)

*

Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (2010) (for Securities whistleblowers)

*

Military Whistleblower Protection Act

It is apparent that US has adopted a more specific approach in protecting the Whistleblower.

THE BRIBERY ACT 2010

The Bribery Act 2010, which came into force in July 2011, contains a new strict liability corporate offence that applies where an organisation fails to prevent bribery by a person "associated" with it, including employees (section 7). The organisation has a defence if it can show that it had in place "adequate procedures" designed to prevent bribery. Guidance from the Ministry of Justice stresses that this would include having effective whistleblowing procedures that encourage the reporting of bribery.

Prior to the Act, British anti-bribery law was based on the Public Bodies Corrupt Practices Act 1889, the Prevention of Corruption Act 1906 and the Prevention of Corruption Act 1916, a body of law described as "inconsistent, anachronistic and inadequate". Following the Poulson affair in 1972, the Salmon Committee on Standards in Public Life recommended updating and codifying these statutes, but the government of the time took no action. Similar suggestions were brought up in the first report of the Committee on Standards in Public Life established by John Major in 1994, and the Home Office published a draft consultation paper in 1997, discussing extending anti-bribery and anti-corruption law. This was followed by the Law Commission's report Legislating the Criminal Code: Corruption in 1998. The consultation paper and report coincided with mounting criticism from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, who felt that, despite the United Kingdom's ratification of the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention, its bribery laws were inadequate.

A draft Bribery Bill was announced in the 2002 Queen's Speech, but was rejected by the joint committee examining it. A second consultation paper was issued in 2005 examining the committee's concerns, before the government announced in March that "there was broad support for reform of the current law, but there was no consensus as to how this could be achieved". Following a white paper in March 2009, the Bribery Bill, based on the Law Commission's 2008 report Reforming Bribery, was announced in the Queen's Speech. Initially given all-party support after its introduction by Jack Straw in 2009, the Bill was, according to The Guardian, subject to an attempted filibuster by Members of Parliament from the Conservative Party. This followed pressure from the Confederation of British Industry, who worried that the Bill in its original form would hamper the competitiveness of British industry.

The Bill was given Royal Assent on 8 April 2010, becoming the Bribery Act 2010, and was expected to come into force immediately. The government instead chose to hold several rounds of public consultations before announcing that it would come into force in April 2011. Following the publication of guidance by the Ministry of Justice, the act came into effect on 1 July 2011. The Ministry of Justice also released a Quick Start Guide, which highlights some key points of the Act. The Quick Start Guide also suggests companies to consult relevant bodies for advice, including the UK Trade and Investment, and the government sponsored Business Anti-Corruption Portal. In October 2011 Munir Patel, a clerk at Redbridge Magistrates Court, became the first person to be convicted under the Bribery Act, along with misconduct in a public office.

POLITICAL INFORMANTS

Informers alert authorities regarding government officials that are corrupt. Officials may be taking bribes, or participants in a money loop also called a kickback. Informers in some countries receive a percentage of all monies recovered by their

government.

Lactantius described an example from ancient Rome involved the prosecution of a woman suspected to have advised a woman not to marry Maximinus II:

"Neither indeed was there any accuser, until a certain Jew, one charged with other offences, was induced, through hope of pardon, to give false evidence against the innocent. The equitable and vigilant magistrate conducted him out of the city under a guard, lest the populace should have stoned him... The Jew was ordered to the torture till he should speak as he had been instructed... The innocent were condemned to die.... Nor was the promise of pardon made good to the feigned adulterer, for he was fixed to a gibbet, and then he disclosed the whole secret contrivance; and with his last breath he protested to all the beholders that the women died innocent."

BLOWING

THE WHISTLE - More protection should be given to whistleblowers by the

courts and with changes to stature to ensure that dirt does not just get

swept under the carpet. Imagine if it was possible to sweep away evidence

of being told and being told about crimes in public, by asking a court to

grant an injunction preventing disclosure. Disclosure is a right protected

by Article 10, so long as the disclosure is accurate - and we would

recommend - supported by documentary proofs. That way any fair minded

court abiding by Section 6 of the Human Rights Act 1998, could not be

persuaded to part any citizen from his Convention right to blow the

whistle. The danger is always that in their frustration as perfectly

reasonable moan about lack of justice in Sussex, may stray into a

bolstered view, rather than stick adamantly to the facts.

WEALDEN'S

COVER UP POLICIES

Responsible

Council's have in place a 'Whistleblowing' scheme whereby wrongdoing by

any member of staff may be reported to a higher authority with

impunity. Employees are encouraged to use the scheme to help

prevent small mistakes becoming major issues, where a cover-up absorbs

many times more resources, than a simple admission early on.

Persons

who suffer pressure from colleagues as a result of reporting suspected

wrongdoing, may receive unlimited compensation and in a growing number

of cases, have already done so. The Official Secrets Act does not

prevent any person whistle blowing.

In

reply to questions asked as to implementation of such a policy,

Wealden's Chief Executive(s) confirmed they had no such policy in

place. We ask why? It seems that Council's who have a lot to

hide (hence fear) fight shy of implementing any policy likely to reveal

wrongdoing.

THIS

SITE CONTAINS MANY EXAMPLES OF THIS COUNCIL'S UNREASONABLE BEHAVIOUR - With

thanks to Action Groups across the country for the supply of real case

history and supporting documents. *THAT THE PUBLIC MAY KNOW*

Vicarage Lane, Hailsham,

East Sussex, BN27 2AX T: 01323 443322

Pine Grove, Crowborough, East Sussex, TN6 1DH T: 01892

653311

CONTACT

OUR WEBMASTER

|