|

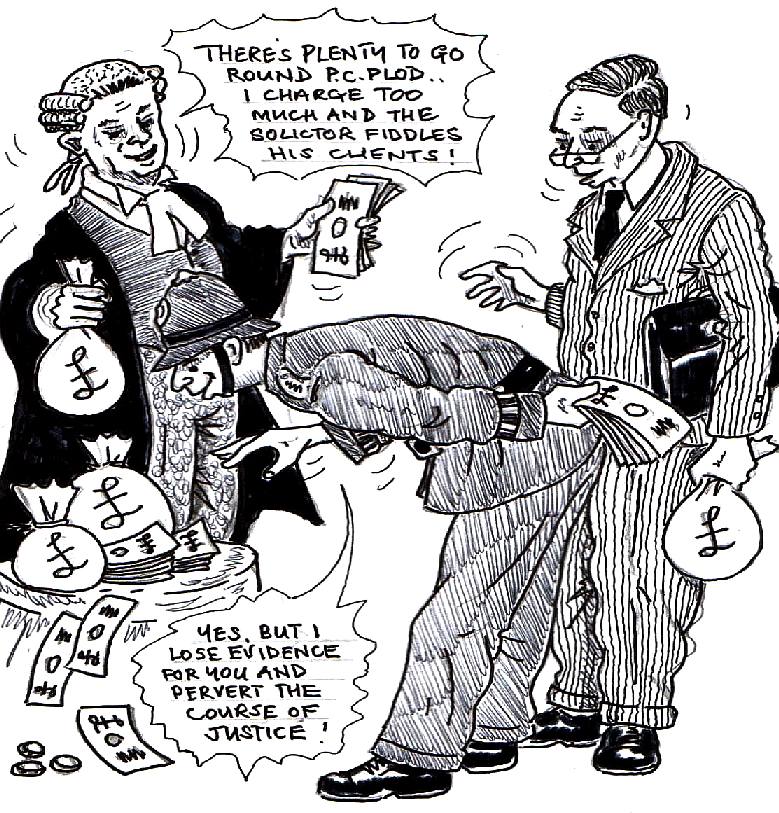

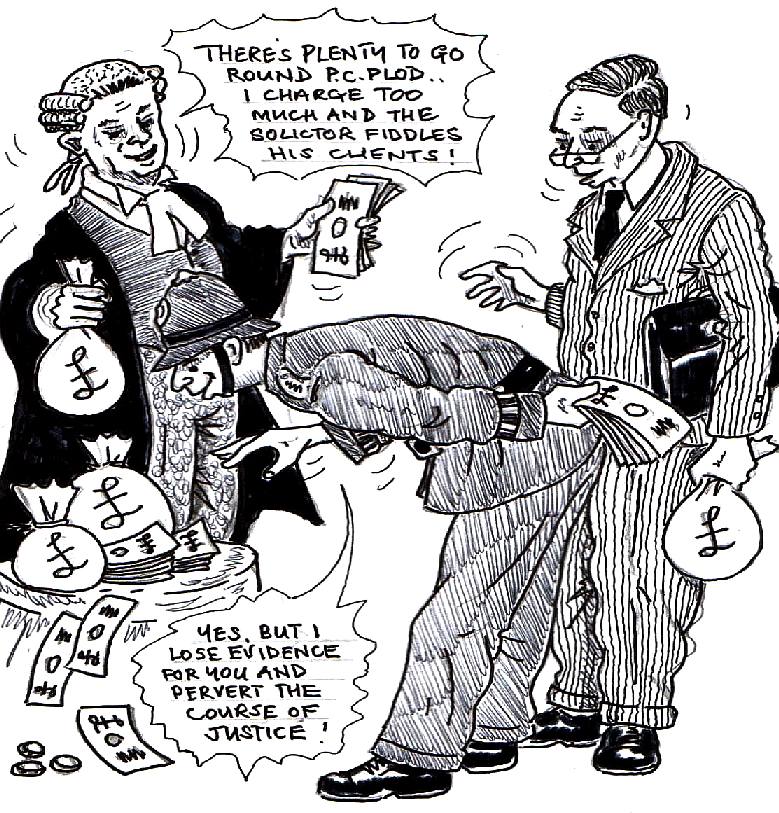

ARMED

& DANGEROUS - There

are hundreds of policemen pounding British streets that will be involved

in crafting the evidence to obtain convictions, or otherwise cover up

their mistakes. Others will use their position of trust to groom

vulnerable children and adults for sex. Perhaps helping them to gain

revenge and then using that conspiracy to lever favours at a later date.

In other cases masonic influence infects the British justice system,

injecting discriminatory practices into an institution that should be

above reproach. Police officers are immune from murder

charges so long as it is in the line of duty, but what about when

raids are organised on trumped up

intelligence. Any copper can do that, raid the premises of an

innocent man - perhaps an inconvenient

whistleblower - and blow their problem away.

Surrey

police were involved in the injunction to muzzle Matt

Taylor. They are

attempting to use the same tactics on John Hoath. It appears, with the

assistance of Weightmans LLP, solicitors and Gilly (Gillian) Jones.

They

were also involved in not fully investigating the facts relating to Donald

Wales and the issue of a trademark agreement by way of a Deed of

Covenant to Nelson Kruschandl, where Mr Wales claimed he'd not sent such

a document to Mr Kruschandl, or in the alternative that it was not a

valid document, despite the fact that his trademark attorneys, Marks

& Clerk, had confirmed to the Herstmonceux entrepreneur that the

Agreement between the parties was a stand alone document.

Surrey

police worked with Sussex Police

to raid Mr Kruschandl's premises, in the process smashing down four

doors and frames and another high security padlock, but they failed to

search Mr Wales's home for an Agreement that Mr Kruschandl had supplied

to them at least a year earlier. The difference in case handling is

called bias. Bias leads police to conclude that a person is guilty and

only to look for evidence to convict, rather than sealing a crime scene

and collecting evidence that shows a suspect is innocent.

In

the case of Nelson Kruschandl, Gordon

Staker, Jo Pinyoun and James

Hookway were sent to gather evidence to convict Mr Kruschandl an to

a trumped up allegation of sexual assault, when it appears that they

ignored and may have even advised a psychiatric nurse to hide evidence

and not mention it, being a work diary that proved a lack of opportunity

as had been claimed.

The

facts speak for themselves. Gordon Staker and his team failed to secure

video tapes belonging to the claimant that proved she was an avid

follower of The Bill and Casualty, where she'd claimed in interview that

she did not know that sexual assault and rape was wrong, and where those

television programmes routinely carried episodes about child sex,

prosecutions and the like. Hence, the girl was lying about that, and

only made up her story about being abused after all other attempts by

her to force the defendant to remain with her mother had failed. The

girl and her mother had warned him not to leave their family. The poor

chap had no idea what these females had is store for him. Sussex police

and social services knew that the girl and her mother were both

emotional putty in their hands. Wealden and the former councillor who

was angry at the calling off of the engagement to his daughter, were of

course delighted that their long-term adversary was being set up for a

conviction.

Gordon

Staker and his team failed to secure the girls computers and failed to

secure the mother's work diary. We conclude from the failure to secure

these items that the investigation was either grossly negligent or a

deliberate attempt to pervert the course of justice. Either way, Sussex

police is guilty of a malicious prosecution and those officers should

face disciplinary action, along with their superiors.

THE

SPECTATOR 7

MARCH 2015 The shocking truth about police corruption in Britain

It’s a growing problem. But they’re hunting whistleblowers instead

Imagine you lived in a country which last year had 3,000 allegations of police corruption. Worse, imagine that of these 3,000 allegations only half of them were properly investigated — because for police officers in this country, corruption was becoming routine. Imagine that the police increasingly used their powers to crack down not on criminals but on anyone who dared speak out against them. What sort of a country is this? Well, it’s Britain I’m afraid — where what was once the finest, most honest service in the world is in danger of becoming rotten.

Some of this was revealed in a little-noticed report by HM Inspectorate of Constabulary, which went on to deliver some even more shocking news. Nearly half of 17,200 officers and staff surveyed said that if they discovered corruption among their colleagues and chose to report it, they didn’t believe their evidence would be treated in confidence and would fear ‘adverse consequences’. This appalling lack of protection for whistle-blowers — often amounting to persecution — has become commonplace throughout the public services and creates a climate in which dishonesty and malpractice flourish.

The second report, compiled by the Serious Organised Crime Agency, bears this out. It says there has been a sharp increase over the past five years in the number of police officers dealing heroin, cocaine and amphetamines and an equally startling rise in the number of officers abusing their power ‘for sexual gratification’ — in other words bullying or cajoling suspects, witnesses and even victims into having sex with them.

Just this week, in fact, it emerged that the Met suspended 73 coppers, community support officers and other staff on corruption charges in the past two years. They cited drug crimes, bribery, theft, fraud, sexual misconduct and — everybody’s favourite — un-authorised disclosure of information. Eleven were convicted in court, but what happened to the others? The Met spokesman said rather blandly that some were allowed to resign or retire (presumably with full pension rights) and some were dismissed.

This rise in corruption and the apparent reluctance of police chiefs to fight it is a toxic combination. As ever, chief constables blame lack of resources for not being able to pursue inquiries into claims of malpractice. But what could be a greater priority than ensuring that their own officers are not breaking the law? These same police chiefs seem to find endless funds to pursue ancient sex abuse allegations, chase people who say unpleasant things on Twitter and prosecute journalists.

The vast majority of Britain’s police do a sometimes extremely arduous job with honesty, skill and good humour. But corruption left unchecked can infect entire forces. Anyone who doubts this need only study the lessons of the not-too-distant past.

Forty-five years ago the Times splashed across its front page a sensational story that led ultimately to what became known as ‘The Fall of Scotland Yard’. Under the headline ‘London policemen in bribe allegations’, it revealed a tale

The story, backed by taped conversations, bluntly accused three Yard detectives of planting evidence and taking back-handers from criminals ‘in exchange for dropping charges, being lenient with evidence in court, and for allowing a criminal to work unhindered’. If it had been just those three rogue officers, the story might quickly have been forgotten. But the tapes hinted at a far more endemic culture of graft and criminality.of corruption that came as a profound shock to a nation accustomed to seeing its constabulary through the prism of Dixon of Dock Green and Z Cars. A leading criminal lawyer of the time remarked: ‘It was like catching the Archbishop of Canterbury in bed with a prostitute.’

Over the next few years, the Obscene Publications Squad was exposed as a tawdry protection racket extracting regular tithes from pornographers and Soho club-owners; drugs squad officers were shown to be running illegal cannabis deals; and half the Flying Squad was in the pay of criminals. These were not the clandestine activities of a few low-ranking detectives on the take. Whole squads were involved and the seniority of some of those taken down at the Old Bailey was shocking. In the words of trial judge Mr Justice Mars-Jones, it was ‘corruption on a scale that beggars description’.

The exposures of these corruption rackets had one thing in common — they were all revealed in the first place by the efforts of Britain’s free press. But these journalists could not have achieved all they did without the help of whistleblowers. Some of these were pornographers and criminals tired of being milked and intimidated, but others were rank and file police officers disgusted by the greed and criminality of so many of their peers.

The tragedy is that 40 years on, honest policemen in a similar position would fear arrest and imprisonment for even approaching a journalist without permission, despite the clear public interest in their doing so.

The police appear to be retreating into a bunker of secrecy and paranoia where all news must be ‘managed’ and freedom of information is considered a threat. On its website — alongside some vacuous rubbish about ‘declaring total war on crime’ — the Met claims to be committed to carrying out its duties with ‘humility’ and ‘transparency’.

Could anything be further from the truth? With its constant leak inquiries, harassment of whistleblowers and journalists, and scandalous misuse of terror legislation to tap the phone records and emails of ordinary citizens, the Met is probably more authoritarian and opaque than at any time in modern history. This culture comes directly from the top.

Being Commissioner of the Met has long been the most difficult job in policing, but there have been some good ones. Robert Mark, the Normandy veteran who cleaned out the Yard’s Augean stables in the 1970s; Ken Newman, a steely, austere man who served in Palestine during the emergency and headed the Royal Ulster Constabulary before re-organising the Met into a modern force; and the thoughtful Paul Condon, whose tenure came to a turbulent end with the Stephen Lawrence inquiry but who was arguably the cleverest of the lot. Each had his strengths and weaknesses but they all knew that a free, well-informed press was a cornerstone of policing in a democracy. Informal contact was generally encouraged, and in more than ten years as a crime correspondent in the 1980s and 1990s, I don’t recall a single leak inquiry or junior officer being disciplined for passing information to newspapers in good faith.

These men had respect for the office of constable — not least because they had all spent years on the front line before rising through the ranks. And they believed that part of their duty of accountability was to keep the public properly informed of what they were doing and why.

The present generation of police chiefs come from a very different breed. Fast-tracked and homogenised from an early stage, they can be difficult to tell apart. Often laden with degrees in law, business and ‘criminology’ accumulated during their police careers, they are more managers than police officers — managers of budgets, managers of public relations and, most importantly, managers of risk to their own careers. They speak in the obscure, vapid jargon of stakeholder engagement, paradigm shifts and proactivity. So much for transparency.

The present Met chief, Bernard Hogan-Howe, is of this ilk. He may develop into a great commissioner but the signs so far have not been promising. He has a pet theory which he calls ‘total policing’ (apparently based on the ‘total football’ played by Holland in the 1970s). It’s mainly harmless drivel about coppers having to play in all positions. But it contains an extremely sinister subtext. Explaining the philosophy a few years ago, he said it meant that ‘no legal tactic is out of bounds’ in the investigation of crime. Reasonable enough, one might think at first glance, but the problem with this catchy little mantra is that it takes no account of proportionality.

One of Hogan-Howe’s first moves after arriving at the Met was to use the Official Secrets Act to try to compel a Guardian journalist to reveal the source of a story about celebrity phone hacking. The Official Secrets Act is meant principally to be used to trap spies, traitors and those who threaten the defence of the realm — not reporters going about their legitimate business. This was a disproportionate and oppressive use of the law.

Similarly, legislation designed to combat terrorism and serious crime, such as the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act, is used with alarming frequency by Hogan-Howe and other police chiefs to snoop on the internet and phone records of law-abiding citizens. This is the tactic of the police state. Not so much total policing as totalitarian policing.

Naturally, the ‘total policeman’ also favours more armed officers on routine duties, more Tasers and the mainland deployment of water cannon to disperse rioters, despite the fact that its use in Northern Ireland tended to inflame tensions rather than cool them. He also favours police officers being taken off the electoral roll and not wearing their uniforms on the way to and from duty shifts.The rise in Islamist terrorism has increased the threat level for soldiers and the police and sensible measures must be taken to combat that. But just as great a threat was posed over 30 years by the Provisional IRA and its offshoots without panic reactions. Hogan-Howe appears to be taking the police away from being a service and back towards being a coercive force. This is starkly demonstrated by the pursuit of journalists in the wake of the baleful Leveson inquiry. It has been driven to the point of absurdity, with up to 200 officers involved at one time and dozens of hapless hacks put before the courts, some on the flimsiest of charges.

All this has wider implications for the integrity of the police. One of the consequences of a heavy-handed police leadership stretching the law and using their power to bully and intimidate is that rank and file officers are encouraged to think they can do the same. Once ordinary officers start abusing power, a culture of semi-criminal behaviour becomes normal and whistleblowers are treated not as honourable but as traitors.

Judging from the recent reports, this may already be happening to an alarming degree around the country. The lessons of history suggest that if police chiefs are serious about neutralising the threat of corruption, they will need the help and support of the press. They will only get it if they start talking to journalists — instead of looking for reasons to arrest them.

Neil Darbyshire is an assistant editor at the

Daily Mail. He is a former deputy editor of the

Daily Telegraph, where he was crime correspondent for many years.

PAUL

WHITEHOUSE & SUSSEX POLICE

As

to the integrity of Sussex police and their chief constables, we should

look at the investigation of the shooting of James Ashley

under the lead of Sir John Hoddinott.

The Wilding report found a complete failure of corporate duty by Sussex police. The

Hampshire inquiry concluded that three police officers lied about intelligence in order to persuade Deputy Chief Constable Mark Jordan to authorise the raid. The report found that the raid was

"authorised on intelligence that was not merely exaggerated, it was determinably false ... there was a plan to deceive and the evidence concocted."

The report also showed that the guidelines on firearms put together by the Association of Chief Police Officers was breached. Experts on firearms and the law told

Kent police that even if the intelligence had been correct, the firearms should not have been authorised.

The chief constable was castigated. Sir John Hoddinott concluded that Paul

Whitehouse, the then chief constable,

"wilfully failed to tell the truth as he knew it, he did so without reasonable excuse or justification and what he published and said was misleading."

Sir John found evidence against Deputy Chief Constable Mark

Jordan. That included criminal misfeasance and neglect of duty, discreditable conduct and aiding and abetting the chief constable's false statements. There was suggested evidence of collusion between some or all of the chief officers and an arguable case of attempting to pervert the course of justice.

These statements were contained in those investigation reports. The reports have been kept secret - apart from the leaks made to the press - and have never been available for public scrutiny.

CONTACT

SURREY POLICE

Surrey

Police

Headquarters

......

In an emergency, when life is in immediate danger or a crime is in progress, call 999

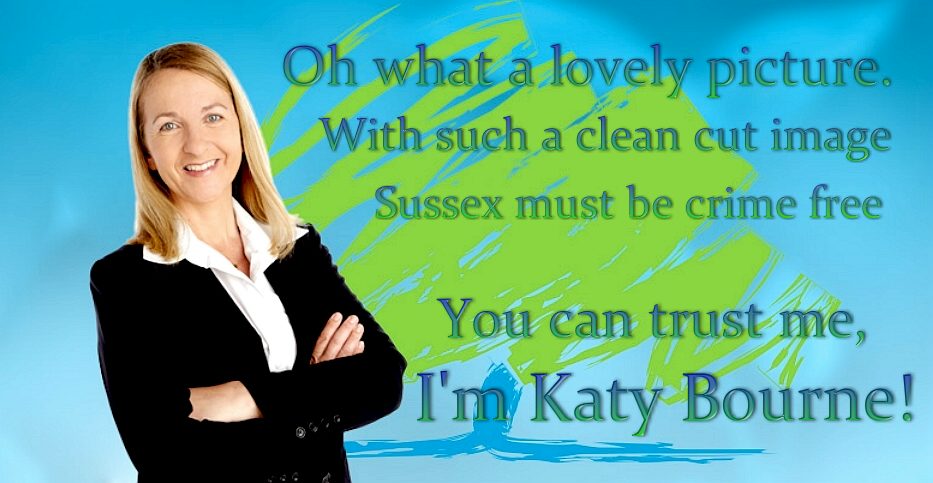

KATY

BOURNE - Was elected

Crime

Commissioner, taking office with an oath to serve

the public interest. That is an oath that many are now questioning, where

she appears to be serving Sussex Police instead of policing the

organisation that has come under such flack for their blatant refusal to

investigate so many complaints of malfeasance in public office. What is

plain is that where there is criticism of her alleged inaction, that she

works with other forces to quash what many might agree is freedom of

speech. In the case of Matt Taylor obtaining an injunction and in the

case of John

Hoath (gun

crime allegation) threatening an injunction.

Giles

York is the chief constable of Sussex

Police taking over from a long chain of chief constables,

including Paul Whitehouse, who was finally

forced to resign after the Home Secretary insisted that he should go for

bringing the force into disrepute from his attempt to cover up the Jimmy

Ashley murder. Each

time one chief resigns, the next candidate learns from the mistakes of

his predecessor and makes effort not to be tripped up in the same way.

Unfortunately, that is not helping the situation, where in-effect Mr

York has nobody looking over his shoulder to make sure that he is not

breaking the law. The most common way of breaking the law, is simply

doing nothing when a crime is reported - so becoming party to the crime,

as with the Petition

scandal in 1997.

LINKS &

REFERENCE

http://www.report-it.org.uk/your_police_force

https://www.kent.police.uk/

A

- Z OF SUSSEX POLICE OFFICER INVESTIGATIONS

Aran

Boyt

Chris

Sherwood

Colin

Dowle

Jo

Pinyoun

Joe

Edwards

Giles

York

Gordon

Staker

James

Hookway

Kara

Tombling

Ken

Jones

Martin

Richards

Paul

Whitehouse

Robert

Lovell

Sarah

Jane Gallagher

Sir

Ken Macdonald QC

Timothy

Mottram

This site is protected under

Article10 of the

European Convention on Human

Rights and Fundamental Freedoms.

FAIR

USE NOTICE

This

site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been

specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such

material available in our efforts to advance understanding of

environmental, political, human rights, economic, scientific, and social

justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a 'fair use' of any such

copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright

Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this

site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior

interest in receiving the included information for research and

educational purposes.

For

more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If

you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your

own that go beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the

copyright owner.

Paul

Whitehouse (1993-2001) Ken

Jones (2001-2006) Joe

Edwards (2006-2007) Martin

Richards (2008-2014) Giles York (2014

>>)

|